Trading the stock market is a complex and ever-changing challenge. Here are seven common trading strategies investors use to navigate it.

Do you consider yourself an investor, or a trader? If you’re the type who prefers to buy and sell shares in the stock market often, instead of holding onto an investment perhaps for several years at a time, you’d probably be considered a stock trader.

You may have heard the terms ‘passive’ and ‘active’ investing.

Passive investing is generally long-term investing. You might research and value a stock, invest in some of its shares, and leave that investment alone for many years to let it appreciate in value.

Active investing is the opposite.

Active investing is the domain of the trader, as opposed to the investor.

Traders don’t look for long-term investments. Rather, they buy and sell stocks with the objective of making a quick profit from short-term price movement.

Some traders may make hundreds or thousands of trades a day, aiming to cycle their capital between positions — often looking to profit from both upward and downward price movement.

In this post, we’re going to introduce some of the essential components of trading strategies, from some of the common terms and ideas to important factors every trader, indeed every investor, should be familiar with.

Then, we’ll cover seven commonly used stock trading strategies traders of many different kinds are using in the stock market today.

Essential Components Of Every Trading Strategy

Trading in the stock market — regardless of which trading strategy you choose — requires a significant amount of knowledge.

Even beginning traders should invest substantial effort into educating themselves on the processes and terminology of the market and the wide variety of assets trading on it.

Volume: Volume refers to the amount of shares being bought or sold in a given stock at a given time. Most stock charts will show you the volume relative to the price movement — often with a bar graphic displayed over the price movement line. Volume shows you how much money is changing hands for that asset in the market.

Liquidity: Liquidity relates directly to volume. The more shares are being exchanged in a stock, the easier it should be to find a buyer or seller to trade with. Low liquidity might mean it takes time to execute your trade — which could mean the price shifts while you wait.

Volatility: This is the extent to which the stock’s price moves up and down. If the share price moved between, say, $100 and $105 over a one-month period, you’d say it showed low volatility compared with another that moved between $5 and $50 in the same timeframe.

Float & Short Float: When you hear traders talk about the ‘float’, they’re referring to the number of shares available to the public to buy and sell. The float has an effect on a stock’s liquidity. The ‘short float’ refers to the number of available shares that have been borrowed for short selling (this is a key indicator of short interest).

Long and Short: You may have heard the phrase ‘going long’ or ‘going short’. These are stock market terms for betting on a stock rising or falling in price. A ‘long’ position is where you buy shares and aim to sell them at a higher price. A ‘short’ position is where you borrow shares and agree to sell them at a lower price, capturing the difference as profit.

Moving Average: Traders will use the moving average to determine a stock’s trend over a given time frame. Many charting tools will allow you to set and view a moving average line over the price movement. This allows you to ‘zoom out’ and get a different perspective on a stock from price alone.

Stop Loss: Traders and investors alike commonly use stop loss orders to protect their capital. When you enter a trade with your broker, you can set that order to automatically sell you out of part, or all, of your position when the stock falls to a given price. This can save you losing more capital on a losing trade. It can also result in being ‘stopped out’ of a good trade during temporary price drop.

Limit Order: The limit order works similarly to the stop loss order. But in this case, you enter the trade with the condition to buy shares at a certain price. Say you’re keen to buy 100 shares in Stock X, but you don’t want to pay the current price of $20, you can enter a limit order so that if the price comes down to $15 within a given time frame, your broker will try to buy you those 100 shares.

These are just some of the key terms you need to be familiar with when entering the stock market as a trader or investors.

Remember, all investing carries risk and it’s vital to educate yourself, seek advice and be clear about the risks to your capital when you enter the market.

Seven Commonly Used Stock Trading Strategies

Now that we’ve covered some of the basics above, let’s get into the actual trading strategies you can choose from when looking to make money in the stock market.

Day Trading: Fast, High Impact Buying & Selling

You’ve probably heard of day trading. Day trading is exactly what it sounds like — a style of trading where all the buying and selling occurs within a single trading day.

The idea with day trading is to use large amounts of capital — and often ‘leverage’ (money borrowed for trading) — to profit from intraday price movements in stocks.

Day trading depends heavily on technical analysis. In other words, interpreting stock charts to determine the likelihood of small price movements one way or another.

Day trading relies heavily on technical analysis. The day trader tries to predict a short-term price movement, and bet a large amount of capital on that movement with a view to closing out the trade that same day.

For example, a day trader might calculate Stock X is going to increase from $10 to $10.25 that day.

They might put $100,000 of their own money into that trade, plus another $200,000 of leverage (borrowed money from their broker). They’ll probably use a stop loss to protect against critical losses, too.

If that price move does play out, it’s only a 2.5% gain. But with the $300,000 they traded with, that’s a $7,500 profit (minus the leverage fee, of course).

That’s day trading in a nutshell! Of course, the potential big rewards come with the equal amount of risk.

Day trading is an often-talked about trading strategy which, like all stock trading strategies, carries with it the risk of losing money.

Position Trading: Looking to Profit From Medium-Term Trend Prediction

While day trading hinges on making trades within a single day, and trying to leverage tiny price movements for big profits, position trading is a relatively slower trading strategy.

Position trading, or ‘trend trading’ is similar to day trading in that the position trader will use charts and technical analysis (ADD TA ABOVE!) to determine whether a stock or market is likely to move up or down.

The difference is that position traders don’t worry about trying to predict prices. Instead, they use an array of tools, calculations and indicators — the moving average being a major one — to determine the trend.

Once they’re satisfied that a stock is trending a certain way, they’ll enter a trade with a view to holding that position until the trend changes.

This could mean they hold a stock for weeks or months. It could also mean they exit with a 5% gain or a 50% return. To the position trader, the length of the investment and the price change don’t matter. What matters is the trend.

Whatever they’ve put their money in, the trend trader monitors the investment’s trend. As soon as they see a clear indication the trend is about to change, they exit the position. They’ll also commonly employ stop loss orders to protect their capital.

Generally speaking, position or trend trading becomes is a difficult trading strategy in highly volatile markets, since it’s more difficult to determine medium and long-term trends when prices are rising and falling dramatically.

Swing Trading: Buying & Selling Based On Changes In Market Sentiment

Day trading is by definition a very short-term trading strategy. Position, or trend, trading is a longer term approach.

Between day trading and position trading, sits the swing trading strategy. Swing trading isn’t about trends, nor tiny movements in price. Rather, the swing trader focuses on changes in market sentiment about particular stocks.

Moving average indicators are key to swing trading. That’s because they help the trader interpret how the market feels about a given stock. Remember, the stock market is largely a measure of how people feel about companies and businesses.

A swing trader employs a particular kind of moving average called the exponential moving average, or EMA. The EMA doesn’t only reflect the average of a stock’s price for a given period. It also factors in the latest data points for that stock.

These might include company announcements, market news or relevant current events that could impact its stock (consider the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic impacted airline and tourism businesses, for instance).

By interpreting these data using the EMA, the swing trader, will try to determine where bullish (optimistic) market sentiment changes, or swings, to bearish (pessimistic) sentiment.

They’ll use that data to time their entry and exit points for a trade — going either long or short depending on the swing and looking to exit a position once they believe the sentiment is set to swing back.

News Trading: Predicting Market Reactions To Current Events

Many trading strategies have a lot in common with each other.

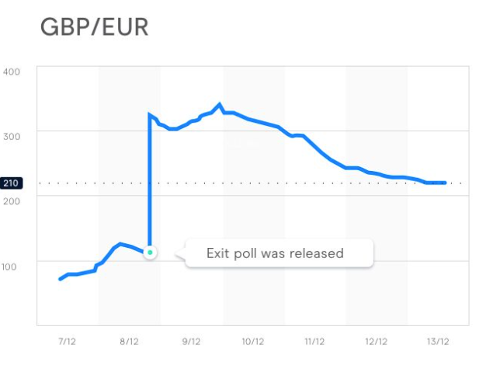

You could think of news trading as swing trading’s cousin. But rather than using technical analysis to determine when prices are likely to move up or down, the news trader monitors current events to predict how a market might react.

Again, consider the airline example above. A news trader might interpret the breaking pandemic stories as a signal airline stocks are about to fall, and either place short trades to profit from the downside, or wait to buy shares after the fall.

See the chart above for an example of how the Brexit news had an immediate impact on the Pound/Euro exchange rate.

News trading requires a lot of research and time. It’s a less exact trading strategy that carries its own unique risks.

Scalping: Aiming to Accumulate Many Quick, Small Gains

Scalping is similar to day trading and trend trading strategies. The scalper will look for quick opportunities to profit using a combination of technical analysis and maybe some trend following.

But, rather than wait for a trend to establish itself, or change, the scalping trading strategy dictates that you get out of every trade fast.

Rather than trading, say, one or two positions a day, you’d trade maybe five or 10, with the aim of gathering up a handful of small wins that amount to a solid return.

The image illustrates how a scalper might approach a trading position.

While there’s no overnight risk (as scalping is a type of day trading), this trading strategy does require discipline, focus, and a tolerance for stress.

Algorithmic Trading Strategy: The Way of Wall Street’s Elite

All the stock trading strategies above have one thing in common: The trader makes the decisions on what they’ll buy and sell, when, and for what reason.

But all those trading strategies can be augmented with another.

In algorithmic trading, the onus is on a piece of software to decide what you should trade.

Algorithmic trading — also called black box trading, or automated trading) involves a computer interpreting huge amounts of market data to determine the best way to trade the market on a given day.

The algorithm produces trading recommendations which you can either manually follow, or automate, depending on the system.

This type of trading relies heavily on the quality of the algorithm you use (and the talent of the people who create it — check out Motion Trader for an example of a very successful trading algorithm).

How To Learn Stock Trading Strategies And Get Started As A Trader

The stock trading strategies we’ve outlined above are just a few of the main types in the market.

There’s many more — and more being created and refined all the time as markets and technologies evolve.

If you want to learn, you have a centuries worth of knowledge to draw on in the form of books, online courses, YouTube channels and more.

The best thing to do is to start learning, talk with other traders and seek to build your knowledge.

If you’re not investing already and are just starting out, you might want to consider this brilliant stock simulator where you can start testing your ideas without any risk to your capital.

However You Choose To Trade The Market, You Must Do This…

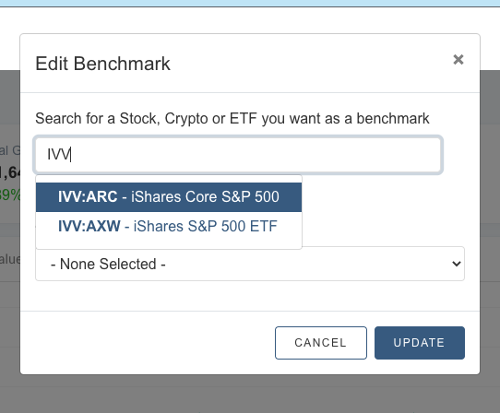

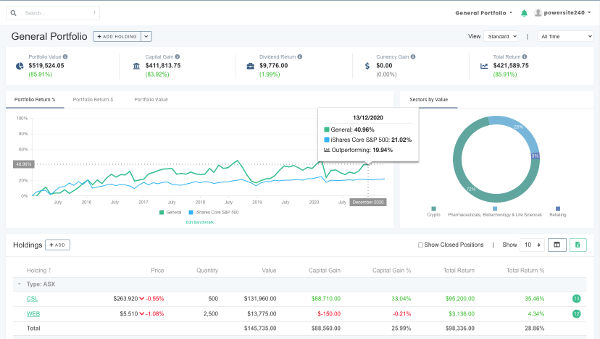

Whether you’re day trading, swing trading or an algorithmic trader, there’s one tool you should make sure you have for your journey: A dedicated portfolio tracker.

When we invest and trade, we often just focus on stock prices and returns. But, in reality, there’s many more factors that impact how much money we actually make (or lose) in the market.

That’s why you need to portfolio tracker that calculates your true, annualized performance for your portfolio and the holdings in it.

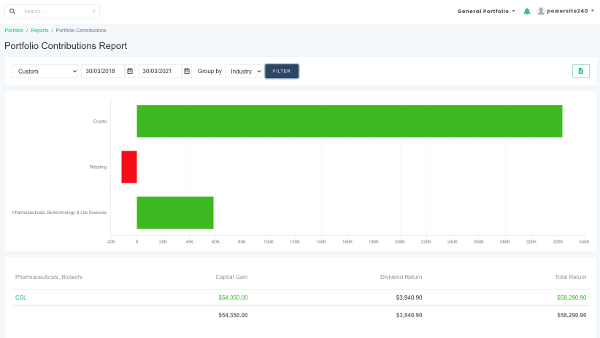

True performance is different from the simple ‘gain’ you’ll see in your trading account. It accounts for how long you’ve held a position, trading fees, currency gain, taxation and dividend income.

The portfolio tracker we run here at Navexa does all this (plus, you can generate a variety of reports, from calculating unrealized capital gains to taxable income, portfolio contributions, and many more).