August 12, 2024

Panic on the streets, or just in the markets?

Dear Reader,

Last week, panic struck.

This is what the internet looked like for investors last Monday:

Source

Rough.

Source

Brutal.

Source

Heavy.

But, we know the media gets plenty of mileage out of hype — particularly the negative type.

So, let’s look at the facts.

Last Monday:

- S&P 500 fell 3% — its worst day since September 2022

- The Dow was down more than 1,000 points, or 2.6%

- The Nasdaq wiped out nearly $1 billion in market cap

To top it off?

The Volatility Index hit levels not seen since the 2008 Financial Crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

Then again, Wall Street’s ‘fear gauge’ has been running haywire of late, so it’s not as straightforward as it might first appear.

But, all up, a pretty decent dose of fear, uncertainty and doubt for the stock market.

A week on from this bolt of panic, let’s look at the factors at play — and, of course, the bigger picture.

To fight inflation is to fuel unemployment

The cost of living crisis that took hold over the past couple of years stemmed, in part, from inflation.

Here’s US inflation over the past century:

Source

By mid-2022, inflation was the highest it had been since the 1980s.

In other words, the value of money eroded, sharply.

Which meant it became more expensive to live.

Which meant central bank intervention.

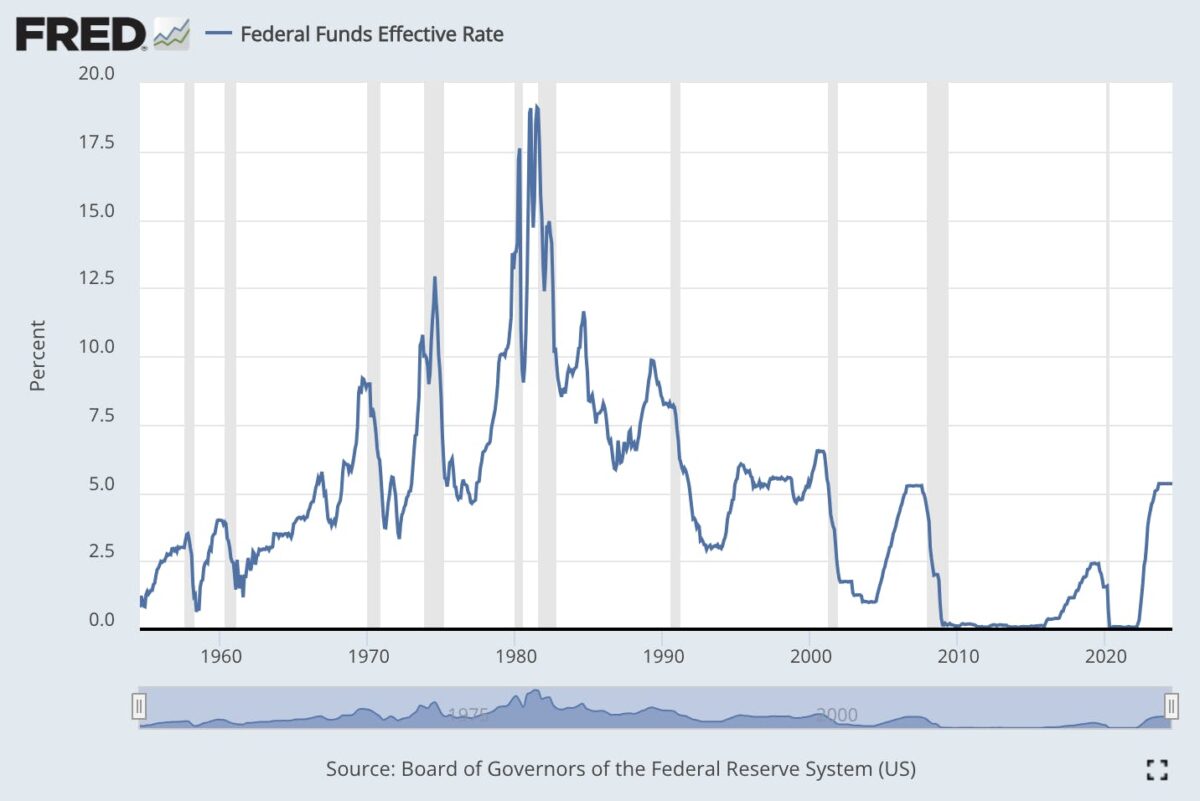

Interest rates, which had trended down since the 1980s — falling sharply after the global financial crisis and then the pandemic — rose again.

You can see in the chart below, we’re only just now back to pre-2008 interest rate levels:

Source

The Federal Reserve (the world’s most influential central bank), goes to war on inflation — too much inflation, at least — by raising interest rates.

According to Phil Rosen:

The Fed’s stated goal is a 2% inflation rate. But it’s currently more than triple that level, which means the economy is running too hot and consumers are spending too much.

The Fed doesn’t explicitly say it like this, but a sure-fire way to crush spending is to raise unemployment — that’s why it’s bad news when the Fed sees more and more Americans joining the workforce each month.

In other words, central banks sometimes try to coax the economy into recession in order to reign in spending and bring inflation back to their target figure.

They expect unemployment to rise. But, in terms of what happened last week:

61,000 new jobs ain’t enough

On Friday, August 2, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the US economy added 114,000 jobs for the month of July.

On the face of it, you’d think more than 100,000 new jobs would be a good thing.

That’s 3,225 Americans starting a new job every day of the month.

That’s growth, right? Wrong.

The part of this equation that spooked the markets last week was the gap between economists’ projections, and the reality.

Everyone thought there’d be 175,000 new jobs created.

Instead, they got a 61,000 shortfall.

It’s like when a listed company forecasts its quarterly profits.

They might tell investors they expect to make a billion dollars.

But if they then only make $750M, it’s the $250M shortfall that makes the headlines, not the actual profit.

And this, of course, is in part down to the stock market being a place where people bet on the likelihood of future outcomes.

Hence the fear, panic and swift erosion of billions of dollars in valuations across both stocks and crypto.

A perfect storm, or a bump in the road?

There were other factors driving Monday’s crash.

Japan’s stock market collapsed 12% — the most it’s fallen in a single day for nearly 40 years — wiping out all its 2024 gains.

This came as the Bank of Japan hiked interest rates. This, in turn, impacted the substantial ‘carry trade’ whereby US investors had become accustomed to borrowing Japanese currency at near zero interest rates and then buying up US-listed stocks in a bid for better returns.

Higher Japanese interest rates = less Japan/US carry trade = less money flowing into American stocks.

Add to this a (probably overdue) cooling in the hype around AI and the Big Tech companies that have been riding that wave since late 2022.

And, of course, let’s not forget Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway announced it had sold half its Apple shares, preferring instead to boost cash reserves.

The Wall Street Journal published a fantastic piece last week weighing up whether this is a 1987-style market-only event, or the signs of a deeper, broader economic collapse.

According to James Mackintosh:

‘Just like today, in 1987 investors were on edge and ready to sell to lock in the unexpected profit. The losses are smaller so far, but lucrative trades have reversed, just as they did for the market as a whole in 1987.‘

Bear in mind that there are people pretty high up in the financial world who are convinced we’re in a secular bull market.

Check the chart below and read more about that here.

Thom Benny

@The_Benchmark_

This chart shows the 1950 and 1980 secular bull markets with the 2013 (current) one overlaid:

10:0 PM • Aug 5, 2024

0

Retweets

0

Likes

That’s enough heavy charts and quotes for this week.

I’ll leave you with one of the more insightful pieces of coverage I saw about last week’s short-lived (for now) market bloodbath, from satire news website The Betoota Advocate:

The story is meant in jest, of course. But make no mistake, the stock market has a lot of people on edge right now.

As always, only time will tell whether the bulls or bears are correct this time around.

That’s it for The Benchmark this week.

Forward this to someone who’d enjoy reading.

If one of our dear readers forwarded this to you, welcome.

Until next week!

Invest in knowledge,

Thom

Editor, The Benchmark

P.S. join me over on X where I post daily about the stories in The Benchmark, plus breaking financial news and events (click below):

Unsubscribe · Preferences

All information contained in The Benchmark and on navexa.io is for education and informational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional financial or tax advice. The Benchmark and any contributors to The Benchmark are not financial professionals, and are not aware of your personal financial circumstances.